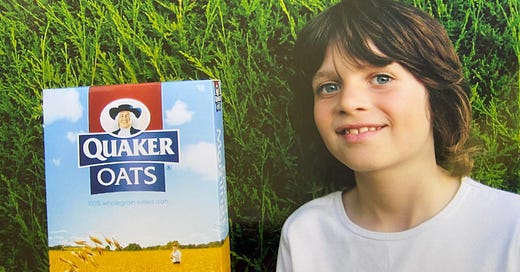

Another of my Big Plans – by now you know these well – came about when I was 10. And before you jump in with predictions, no, it wasn’t the creation of another 12-foot stuffed reptile. It was far more grown up than that. The crux of this plan was porridge. At the time, my dad had been doing some work with a charity raising money to buy a maize mill for a Malawian village. In the spirit of things, I’d read an article in First News – without a doubt the most modish of the children’s broadsheets – about a child elsewhere raising money for a good cause. The content of the article clearly didn’t make too much of an impression, but the fact that you could become a bona fide celebrity – with pictures plastered across the national press – through the simple act of charity made me think it might be worth a crack. As you know by now, as a child, I wasn’t shy of the spotlight. My initial plan was simple: barefoot for a week. How rugged! Sadly, the health-and-safety-powers-that-be at school deemed that far too dangerous. So it was on to Plan B: porridge for a week. This carried slightly less Bear-Grylls-esque playground clout, but it would have to do.

For a week, all I ate was porridge. And God did people know about it. I’ve since been assured that, unlike my memory of that week, I did not accept the challenge with grace and quiet resolve. Despite being the only one to blame for my predicament, at dinner times, I’d relentlessly complain that the rest of my family could enjoy normal food while I had to suffer through yet another bowl of gruel. During lunchtime at school, I’d process piously to the counter to receive my specially prepared bowl and eat it in solemn silence. All of this annoyed my sister immensely. As her frustrations rose to fever pitch, my mum sat her down and confided: it takes an entire village to keep Gandhi in poverty. (The eagle-eyed among you will recognise this as a malaphor – the malaprop of metaphors; the linguistic child of Naidu’s It costs a lot to keep Gandhi in poverty, and the African saying It takes a village to raise a child.)

Now, I’m told this patchwork proverb has recently re-emerged in the Thorpe household. It’s taken a small army of helpers to negotiate the maze of spares and repairs needed to help get Madonna back on two wheels. The customer service teams of various UK-based bike-bits-businesses kindly replaced some parts, after succumbing to my forceful persuasion that six months is a pitiful lifespan for such quality componentry. These deliveries were met by various friends of my parents (the wonderful Wendy deserves a mention), then the separate parcels were packaged together and sent on to a London office, frequented once a month by Ellie’s flatmate and friend, Bella. Bella became the next link in the chain as she graciously couriered the parcel of parts to Barcelona in return for a blog shout-out. Who knew it had become a tradable commodity? Bella, consider this debt paid. Finally, Ellie was on the front line for all Barcelona deliveries: ten in total. That’s a lot of time-window-delivery-slots. Ellie was set to fly out to join me in The Gambia for our next rendezvous on April 6th; with her, she’d be hauling a gargantuan care package. If all went to plan…

While the army of helpers scurried around doing God’s work, I felt rather guilty for barking orders from the back like a plump general. Not that I didn’t try to help, it’s just that frantically searching for pockets of signal in rural Senegal so as to check the status of a part ordered from Germany to Barcelona – and navigating the page in Spanish, no less – quickly proved inefficient. Especially given that my wonderful girlfriend is a bi-lingual powerhouse. So, with the logistics being held up by friends and family, all I had to do was cycle. Simple enough, right?

Wrong. You’d be forgiven for thinking that once you leave the Sahara, you’re out of the woods heat-wise. Well, out of the desert at least. I certainly did. So, it was a bit of a shock to be cycling once more in the mid-forties. I’d agreed to link up with Gui to cross into The Gambia; he’d been steadily pedaling down the coast in trademark style while I’d been running around St. Louis in an attempt to recover lost funds. From St. Louis, I’d plotted a crude, crow-like line (minus the minor diversion) and gobbled the distance to the border like a hungry hippo over two big days… also in trademark style, now I think of it. We’d agreed to meet in Toubakouta, a town just north of the Sene-Gambian border post: Karang. That day, temperatures soared. Without company to reassure me this was indeed f*ing difficult riding, and thanks to the imposed deadline of that evening’s link-up with Gui, I powered on to the point of exhaustion. 20km outside of Toubakouta, I had to pull over, delirious from the heat, and seek cover under a shop veranda. As I guzzled water, I noticed another bike tourer sitting peacefully in the shade. What serendipity. I had a happy exchange with the Dutch cyclist, who assured me the road was all downhill to Toubakouta, and the wind would be behind me.

As I cycled uphill into a headwind for an hour, I wondered whether the heat had rendered my Dutch friend insane. By the time I reached Gui, I was drenched with sweat: a unique phenomenon of the trip so far, thanks to my tropical settings. At least in the desert the heat had been dry. The prospect of a sticky night in the tent sounded less appealing by the second. Luckily, less than half an hour later I was pouring ice-cold buckets of water over my head and scrubbing the accumulated salt from my skin. While I’d been suffering through the day’s riding, Gui had been making friends. In the first act of pure hospitality I’d experienced in Senegal, Amadou and Mamadou invited us to stay with them. After I’d cleaned myself up, we shared iftar – the first meal eaten during Ramadan after the day’s fast – with Amadou’s family. Several courses later, we were marched down the road to Mamadou’s compound, where we were served yet another plate of food, lovingly prepared by his wife. This time, Thieboudienne: a tomato and rice dish with fish and vegetables. Grateful for my famously insatiable appetite – more fierce than ever after a day’s hard riding – and terrified at the prospect of seeming ungrateful, I forced down the last of the rice and sat in a digestive haze watching Tottenham play West Ham on the compound’s small cubic television. It was a truly resourcing moment after the rocky start to my Senegalese dream.

We woke late the next morning, still tired. It was 10 o’clock when we finally hit the road and the sun was already high in the sky. By 12, we were caught in the close concoction of touts, officials, and drifters that swarm border posts. The sun crept higher. As a citizen of the country’s former colonisers, I was spared a visa fee. Gui, on the other hand, a citizen of a fellow colonised nation, had been charged a rather steep $100 which he just managed to scrape together across four currencies. Thanks to the arduous conversion calculations employed by the border official, this was not a quick process, and it was mid afternoon by the time we resumed our riding – now in The Gambia. The heat that day quickly became impenetrable. No matter how much water we forced down, or how many salty peanuts we ate to jack up our bodies’ salt content, we were in a constant state of dehydrated fatigue. A devilish headwind blew hot air directly into our faces as we rode, mimicking the effect of one of Dyson’s latest hair-care innovations. At its climax, the cruel cocktail of heat and wind made cycling for longer than 15 minutes impossible. We’d drag ourselves into the saddle, agree just two more kilometres, and watch the distance tick upwards like an addict watches a bubbling spoon. As soon as the two kilometres had passed, we’d drop our bikes and run to the nearest mango tree, collapsing in a heap under its shading boughs. My latest hard-day-not-a-bad-day philosophy suffered some pretty rigorous stress-testing.

We must have invoked real pity in Gallas as we stood before him, dog-tired and dusty, soaking in the news that the restaurant we’d been pushing for had closed for Ramadan. Without a moment’s thought we were whisked inside his compound, presented to the matriarch for approval, and promptly invited to break the fast with the family. Again, we felt the immense generosity of the Gambian people. We chatted long into the night with Gallas – which we learnt means Great Man; a moniker given to him by the community as an encouragement to live into it. His generosity, hospitality, humility and acceptance were astounding.

We discussed the teachings of the Qu’ran and his own interpretations: the openness of Islam as a religion, its acceptance of people of other faiths or no faith. He told us about his education in the country’s capital, Banjul; the incredulity of his richer classmates at his borrowed shoes and books; his quiet determination to work hard to afford these luxuries. Then we heard about his attempts to enter Europe from Libya; the precarious crossings in small boats; the time spent in prison before being deported back to The Gambia. And we were shown, with immense pride, his basic room in the compound, shared with two brothers: a mattress, a pile of clothes and a laminated certificate for a seven-day entrepreneurship course bearing marks of endorsement from the EU, America and the UN. Perhaps most striking of all, despite his experiences with European border forces, was his response to our profuse thanks; a certainty that If I were in your country, I’m sure people would do the same for me. I’ve retold this story a few times now and, each time, I feel the prick of tears: shameful grief. Gallas, I wish I shared that conviction.

Meanwhile in Europe, Ellie was doing the final roll-call of Madonna’s spares. Thanks to the efforts of the village the grand total stood at: one package from London, nine from Spain. Nine? you ask, I could’ve sworn there were ten. You’d be right. One package had been performing the tantalising dance between delivery office and failed delivery, despite Ellie’s self-enforced house arrest. That one package turned out to be a pretty crucial replacement. Wheels. When it became clear these weren’t arriving, I had some decisions to make. A quick google gave eye-watering figures for delivery to the Gambia; many forums recommended finding a traveler who was already making the trip to courier the parcels. Well, that ship had sailed… or flown.

In the bizarre way of the world, the cheapest option appeared to be for me to fly to Barcelona and collect the wheels myself. Yet, after experiencing first-hand the reality of so many of our fellow humans living in different parts of the world, moving heaven and earth – floating about with the financial and geographical freedom I was lucky enough to be born into – for something as arbitrary as this trip didn’t sit well. If compromises had to be made in the name of reason, then I’d make them. After a day of research and some recon trips to local delivery offices, I found a (relatively) cheaper option. But this option would take time, so I made peace with remaining in the Gambia for a week after my break with Ellie. The village had done more than enough to support my adventure. It was about time I learned the lessons of my youth and pulled my weight on this allegedly solo cycle tour.

I'm just catching up with a couple of episodes while we train our way through Italy. It's a strange paradox that you spot: the less you have, the more you give....... Loving it as always.

I remember that porridge week… it got to us all! But great pic! And to think you watched Tottenham v West Ham!! Hope the wheels have arrived (and the heat is subsiding!) XX