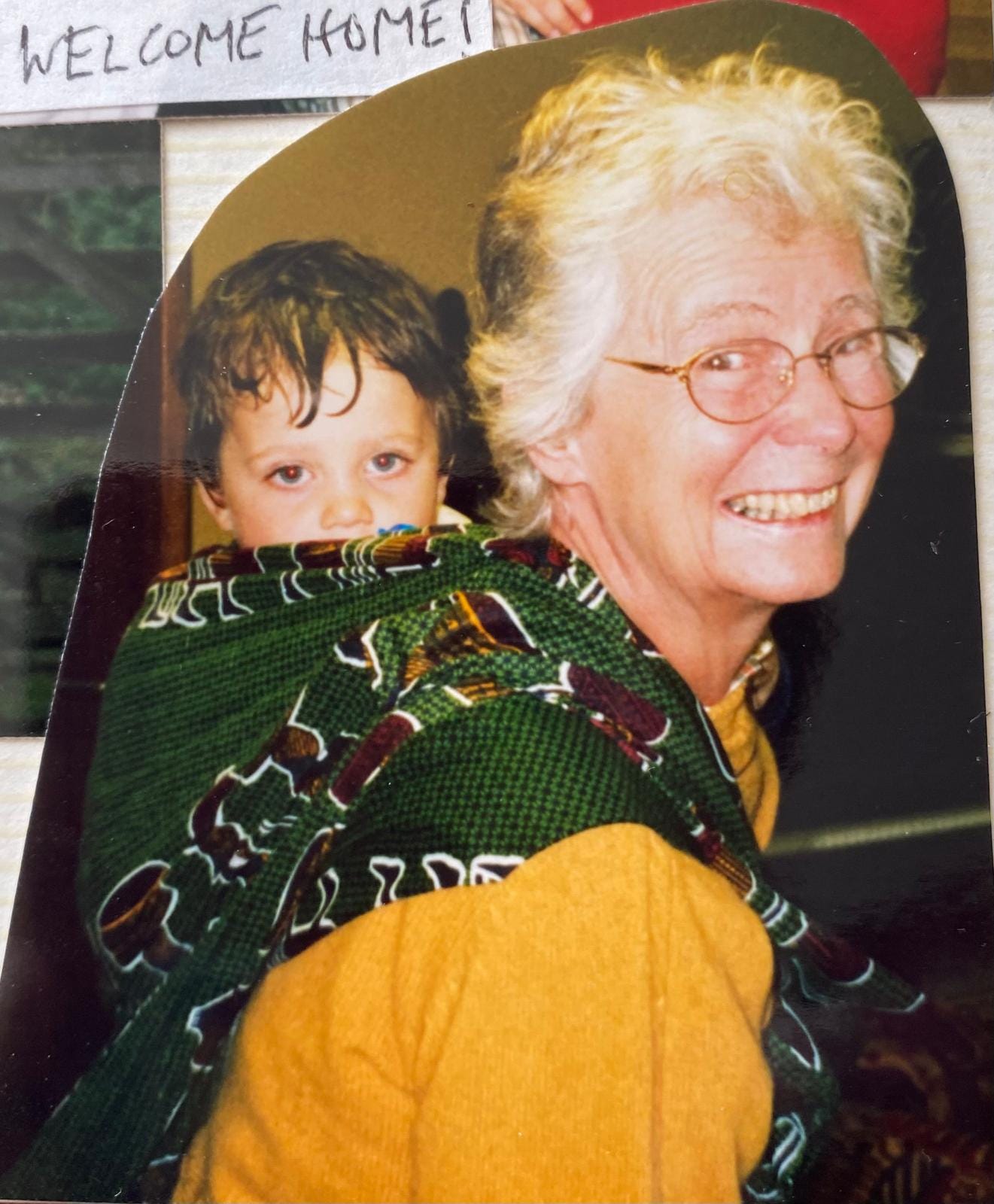

22 years ago, my grandma, at the intrepid age of 68, embarked on her own African adventure. She spent a fortnight visiting a friend—the delightfully alliterative Bishop Boyle—who was, at the time, the Bishop of Northern Malawi. During her time exploring the country known by many as The Warm Heart of Africa, she carried a pocket-size photo album. To connect with as many of The Warm Heart’s hearts as possible, she’d been advised to share a family photo or two, given the significance these relationships hold in Malawian society. Among those she chose was a snap of her two-year-old grandson—a picture she’d captioned just being there. This was, apparently, my response to being asked what are you doing? just before the photo was taken. Pretty pithy for a little nipper. Now I bet she wouldn’t have predicted at the time that, more than two decades later, that very same dot of a grandson would be just being there in Malawi—and not just in the same country, but sitting amongst the very same congregation she’d been welcomed so warmly into. But there I was, sitting in the pews of St. Marks, dressed up in my Sunday best, trying desperately to work out whether the sign of the cross was up-down-left-right or up-down-right-left.

My grandma had reached out to Bishop Boyle a few weeks before to see whether he still had some friends with feet-on-the-ground in Malawi who might be able to help lubricate the shipment of my new wheels. The lessons of my Kenyan customs challenge had stuck: some local know-how was a key ingredient for East African imports. The good news was that Bishop Boyle did indeed still have friends in the diocese, and a great many of them. Before long, a plan was set in motion. It was a slick operation. Within hours, I’d become a link in several email chains and the subject of a WhatsApp group, where I was introduced to the new bishop and his diocesan secretary.

I’m not sure how many of you have ever been in a WhatsApp group with a bishop, let alone two, but let me tell you, from the perspective of someone who’s unfamiliar with the proper convention, it's a parlance minefield. Misters were being prefixed with wild abandon—no longer just Jake, throughout the process I was promoted to the eminent position of Mr. Jake—and Fanuel, the new bishop, was even addressed by some as My Lord. Cramped in the confines of a cab as I bounced through northern Tanzania with a breast-obsessed trucker, I spent considerable time drafting my first message, agonising over each title. When, at last, I plucked up the courage to send it, I received a warm response, along with the friendly correction that the diocesan secretary was called Mr. Mainga, not Mr. Maringa as I’d managed to christen him. Something about falling and first hurdles came to mind.

Thanks to the help of two bishops, and their army of misters, Cape Town was back on the cards. With my destination reinstated, I was finally able to formulate a solid forward plan. I intended to ride down Lake Malawi and pause at various points to soak up excess time until the shipment landed. But, as is often the case in Africa, this solid forward plan soon underwent a phase transition.

International shipping to the continent proved to be a typically viscous process. Despite having been proof-read by my girlfriend—a meticulous maestro of the highest order—the customs form, which was needed for the wheels to be released from Europe, somehow failed to cut the mustard for the experts at UPS. Days slipped by in logistical purgatory as previously provided information was requested, given, requested again, given again, confirmed, inputted, and processed, all at a glacial pace. Given my Spanish stretches scarcely further than bon dia—or is that Catalan?—I was somewhat of a deadweight during the whole process. So, while Ellie spent her mornings listening to the jarringly up-beat music of UPS’ customer service hotline, I retreated to a haven in the Malawian hills where I could wait out this administrative war of attrition.

Mushroom Farm sits on a steep escarpment above Lake Malawi, connected to the shore by an intestinal track of 25 switchbacks. It’s a paradise of hearty food, breathtaking views and lively travellers. But even paradise dulls in the shroud of gloom. I find these times of uncertainty profoundly difficult, so I hunkered down in survival mode, trying, in vain, to detach from the outcome. The fate of forward progress hung in the balance for a week as we wondered whether the wheels would make it beyond Europe or return, once more, to Ellie’s flat.

But, on the seventh day, contrary to the scriptures, the good folks at UPS finally kicked into gear and got on with an honest day’s work. The package was released from the vice grip of Europe and began its journey to Africa. With the wheels back in motion, I could continue my own journey to meet them. After a week lying dormant, both Madonna and I were thrilled to be back on the move. Thankfully, we weren’t forced to retrace the switchbacks down to the lakeshore—a process I’m sure would have spelled curtains for the current wheels—and instead headed further into the Nyika plateau towards Livingstonia, a place we’d heard whispers might sport a tarred road.

Livingstonia was founded in the late 19th century by a group of missionaries, a breed that, at this time, really seemed to be getting busy. Thanks to its heritage as a religious hub—oh all right, Mission Control—Livingstonia was able to divinely cut in line for the privilege of a tarred road in a country of very few. This made for a wonderful morning of cycling, and softened the blow of the afternoon’s stint on the M1—a road which, on the strength of its name, gives every impression that it too might carry some preferential clout, but which instead remains a rutted mess. Still, given I spent half the day moving at a snail's pace, I was able to take in the surrounding scenery. On an arterial highway like the M1, this mostly means road signs, and, thanks to the success of the busy missionaries in the 1800s, these road signs are mostly variations on a fairly predictable theme.

That evening, in Mzuzu, I pitched up at one of Malawi’s more incongruous establishments: an Italian restaurant and campsite called Makondo. After indulging in a hearty dinner—that consisted of about as many courses as a Passover Seder, only with a few less cups of wine—I bedded down for an early night. A clear head and some good sleep were essential: in the morning I was going to church.

This might be considered odd behaviour for a self-proclaimed agnostic atheist, but my grandma had been rightly encouraging that I drop by to meet the team who were assisting with the import of my wheels. And, as I’m sure you know, what granny says goes. However, after my time cooped up at Mushroom Farm, the thrill of being back in the big wide world clearly went to my head and, in my excitement, I managed to sign myself up for rather more than just a flying visit. As the son of a vicar, I’m no stranger to church. But, after about a decade of making my own decisions on the matter—a liberty which has amounted to a fairly poor attendance record—I feared I may be a bit rusty. Add to that the liberal use of misters, sirs and my lords in the diocesan circles of Malawi, and I also suspected that church here is an altogether more formal affair than I’d been used to.

Perhaps thanks to the privilege of my dad being the coach, throughout the church-going days of my youth, I’d gotten away with murder. During a brief stint in the church choir—an elaborate scheme I’d devised with the simple aim of annoying my dutiful and compliant head-chorister of a sister—I regularly abused my prominent position in the pursuit of some high profile misbehaviour. Often, my headphone cable would snake out from under my surplice, through the folds of my ruff and into my ears, blaring hard rock to drown out the less rousing offertory hymns. Some Sundays, I had the audacity to yo-yo down the aisle—back when the mastery of such a skill was the ultimate gauge of playground clout, rather than an arrow in the quiver of an aspiring clown. And once—and I’m certainly not proud of this—I even turned mid-service to one of the tenors, a mild-mannered retiree with several distinguished years of service in the choir, and told him, in full earshot of most of the congregation, to fuck off. Safe to say, such mischief seemed unlikely to fly at St. Mark’s of Mzuzu.

Still, as a British envoy—the eminent Mr. Jake, no less—I was determined to be on my best behaviour, and, of course, make good use of my titular homework. Mr. Mainga had been thrilled to hear of my intentions to join the congregation on Sunday, and had given me the option of the 7am-9am service, or the slightly more indefinite 9.30am service, that could finish anywhere between 12am and sometime on Tuesday. I swung for the safer bet and woke pre-dawn that morning to allow ample time for my commute. I breakfasted on black coffee and donned my Sunday best. Sadly, life on the bike doesn’t lend itself to a great deal of flexibility in the wardrobe department. The best Sunday best I could piece together was a rather garish combination of shorts, a Hawaiian shirt, pink socks and purple Crocs. Still, at least I went to the effort of wearing pants. That’s more than can be said for most days. And the shirt, which had been missing most of its buttons for several weeks now, had even undergone some last minute surgery to prevent the embarrassment of a mid-service nip-slip. In the end, I decided that Sunday best was a relative concept and hopped on Madonna, compass set for the house of the Lord.

I arrived in the nick of time and took a pew, still panting as the service started. The first surprise—and a welcome one at that—was that the service seemed to be in English. I later learnt that the 7am service is in English, whereas the 9.30am is in Chichewa. Mr. Mainga’s generous invitation had omitted this particular distinction, leading me to suspect that either he overestimated my fluency in the local language, or that he simply believed the word of the Lord is universally understood.

Either way, by the time the sermon began, the service might as well have been in Chichewa. It was a theological labyrinth. Still, I appreciated the sentiment, not only because its content seemed a far cry from that of the country’s billboards, but also because it was delivered in a way that washed over me, lulling me into a comfortable daze, rather than requiring acute academic attention. The preacher, however, seemed well aware of this effect, so, to avoid anyone becoming too drowsy, he’d evolved his method to employ punctuating Amen!s after particularly rambling sections. These jolted you from your reverie as you scrambled to respond Amen! in time. If he wasn’t quite satisfied with the verve of his congregation’s reply, he’d repeat the antiphonal until he was. Such audience participation was foreign territory for me, having been raised on a more traditional edition of the Sunday service, and was usually only reserved for Christmas Day when our father—the terrestrial one—would encourage a show and tell of the morning’s haul from the children in the congregation. If memory serves me, I believe one year I was given a mankini… though I can’t be certain if I followed through.

Luckily, as soon as the singing began, we were back on familiar ground. Despite my low-percentage hit-rate of hymn recognition, church music is particularly user friendly. The melodic chorales progress at a pedestrian pace, and knowledge of grade 5 music theory isn’t often required to guess the next note. Like Jay-Z in the 90s, you can hang back a bit, buying time to fumble around until you find the right one. What’s more, hymns are tirelessly repetitive, so, at least by the last verse, you’re really able to belt it out.

After some hymns came the notices. These were comprehensive to say the least. They began with a recital of the itemised revenues and costs of the church’s accounts that month—from retirement packages to pencils—followed by a round of questions. One question that week was about the high cost of the church’s energy bills. Casting an eye over the ribbons of incessantly blinking LEDs draped across every imaginable surface, I could hazard a guess at why. Then came the names of everyone across six churches that had given their tithes, followed by an even longer list of additional donations. This, finally, was followed by an announcement of a workshop on offer in August for the children of the parish who were exhibiting deviant behaviours. I was sincerely grateful that I hadn’t been sitting in these pews a decade earlier, or else I’d no doubt have been signed right up. By the time the notices had concluded—over an hour later—I was both very glad that I’d managed to luck out on attending the English service, and also very relieved that the Sunday Eucharist comes with an integrated refreshment break. Communion arrived just in time to quiet my grumbling stomach, and I steeled myself for the final half hour.

The cherry on the cake of the service came just after communion, when I was asked to come up and address the congregation. This surprise was an altogether less welcome one, not because I have any objection to a moment in the spotlight—by now you’ll know I rather enjoy it—but because I was, all of a sudden, painfully aware that the concept of Sunday best wasn’t universally relative. I crept up to the front, tattooed legs sprouting from my shorts, a good slab of chest protruding from my shirt’s gaping neckline, purple Crocs squeaking on the marbled floor, and prepared to be heckled. I had precisely fifteen seconds to come up with a speech, so, in an attempt to buy some more time, I took a punt at the preacher’s trademark address. Good morning church! I bellowed, sincerely hoping that this wasn’t a right reserved only for the ordained. Good morning! came the hearty response. Phew. I went on to give a brief introduction of me, my trip, and my grandma’s connection to St. Marks. In an attempt to quell my wardrobe anxiety, I imagined the congregation naked. In an attempt to quell their own embarrassment, I can only assume they imagined me clothed.

The following day, after meeting with St. Marks’ parishioners and the teams that run their charitable projects, I set off towards my penultimate Malawian stop, Nkhata bay. I coasted down to the coast—a linguistic crowbar made possible by the fact the whole ride was one long descent—where I met a few friends from Mushroom Farm who were also tracking the same well-trodden trail. Coincidentally, Ollie and Rory—brothers and fellow Brits who’d kindly adopted me in Livingstonia—had also been to church the day before, on the invitation of Donna who worked at their lodge. They too hadn’t got the memo about the distinction between the English and the Chichewa service, and, unfortunately, luck was not on their side. By the time the notices began—a 90 minute affair, all in Chichewa—they made their excuses, and backed, bowing, up the aisle and out the back door. I commend them on their nerve. At least they scored points for long trousers.

At Nkhata Bay, I holidayed—reading, writing, and writhing around one-handed in the waters of Lake Malawi, taking a leaf from Seamus’ book on the subject of Bilharzia prophylaxis. Then, one morning, I received word from Mr. Mainga that the wheels had arrived in Lilongwe. While preparing for my journey down the lakeshore to the capital, I noticed that my incumbent rear wheel had breathed its last. Two spokes had broken on the final stretch to Nkhata, leaving the once spherical rim sitting elliptically at a jaunty angle. Luckily, by then, I was no stranger to a lift. So, at 4am the following morning, I packed up my tent, rode into town, rode back for my forgotten towel, and caught the bus by the skin of my teeth. I rode the six-hour journey down to Lilongwe in a state of relative calm, given that Madonna had been sandwiched so literally in the cargo-hold. No jiggling means no Jiggley.

I arrived in Lilongwe at midday, famished, thanks to my towel mishap costing me the luxury of having any breakfast. Rather tantalisingly, I met one of the army of misters, a Mr. Mwale, at one of Lilongwe’s countless shopping malls, just outside a KFC. After a truly joyous handover—which triggered a chain reaction of messages to all relevant parties—I strapped myself to the enormous package and, in an exercise of immense self-control, turned my back on The Colonel in search of a bike shop. The bike shop closed at 5pm and wouldn’t open again until after the weekend. Sustenance would have to wait. At 4.59pm, after three hours of grease, sweat and the occasional tear, I pumped the last squeeze of air into my tyres and let my stomach guide me back to the bright lights of the city.

I FaceTimed my parents in an attempt to pull my weight in the great dissemination, though it turned out they’d already heard the good news from several sources by this point. In a characteristically perceptive move, my dad—seeing the effect of the saga’s conclusion on the washed-out face on screen—prescribed an immediate treatment of chicken and chips, a Malawian classic. The washed-out face paused for a moment, searching for the button to flip its camera, before the screen filled with the neon homogeneity of the world’s largest chicken shop. Praise the Lord, the good vicar whispered.

A very amusing read Mr Jake xx

Uplifting. Praise be to the poultry and potato.