Before I get into it, I’d like to thank you for your patience. As much as the riding is a feat of physical endurance, I’ve at times underestimated the mental endurance of churning out these blogs—and while the physical can be accomplished with brute force, there’s no such easy breakthrough with the mental. So the final blogs will come, in time, but they’ll come at their own pace. I do hope they’re worth the wait. For now, here’s the end of Blog 40 to ease you smoothly into 41.

Thanks entirely to my legs—and with no help at all from my mind—with 50 kilometres still to ride, I reached tarmac. From here, I put the hammer down, keen to give the shadows of night a run for their money. This tactic proved successful until the final challenge approached: a sheer wall of a pass, soaring 1000 metres up from the valley floor. Just as I stood on my pedals, ready to settle into a calm and consistent cadence for the climb ahead, the object of my speedy flight shifted as a raging bull burst from an adjacent field out onto the road behind me. I screamed and stamped on the pedals with my last reserves of energy, hauling Madonna up and over the ramp ahead and onto the flat beyond where I could escape to safety. As if mirroring my own depletion, the light chose this moment to croak, and my back tyre too gave up the ghost. I was out of light, out of spares and out of energy. And with that, I was shit out of luck.

When in a pinch in an unfamiliar place they say to sit on your suitcase and wait for a solution to present itself. But clearly they aren’t familiar with my particular suitcase’s spotty record of sturdiness. Instead, I laid Madonna gently beside me and perched just close enough that our arrangement might conjure up a similar effect. And conjure it did.

Not five minutes after landing on the suitcase ploy, a pair of high beams cut through the dusky gloom. The truck they belonged to slowed as it approached, coming to a stop just beside me. A man craned through the gap above his half-lowered window—the vehicle was at the stage of life where it had given up on all mechanical functions besides forward motion. After a brief exchange, Madonna was hoisted into the truck’s bed and I jumped into the cab beside my new friend.

Edward was a wiry man. His overalls hung from a sinewy frame—the corporal hallmark of a life of hard labour—and his weathered face did an impressive job at masking his age. Nowadays, as a self-proclaimed peasant farmer, he tended a small plot of land in the valley to supply vegetables to a local boarding school, but it wasn’t the retirement he’d envisioned. After several decades of service to one of Zimbabwe's largest platinum mines, he’d been released without notice, his severance pay appearing not as the promised lump sum of $7,000, but instead as a handful of crumpled bills—barely enough for a full tank of diesel. Now 65, and with nothing more to his name than his house and his truck, he’d begun to farm the land around him as a means of subsistence. But Edward had three children, all of whom he’d worked to put through technical college while earning a steady salary at the mine. They were a source of hope. But hope, I gathered during our short ride together, is a commodity that’s in short supply in Zimbabwe.

Edward had agreed to take me up to Nyamoro Dairy, the evening’s planned stopover, which sat just below the summit of the proud peak at the valley’s head. As we neared the top of the climb, Edward’s beams settled on a small figure in a canary-yellow jersey bobbing up the road ahead. Even without the Christmas tree of interactive displays and flashing gizmos, the figure was unmistakable. I’d caught up with Thijs.

As we pulled alongside my riding companion—who impressively managed to contain the shock of being accosted by an unknown vehicle on an unlit backroad of an unfamiliar country—Edward called out to offer him a lift. Thijs graciously declined, choosing, it seemed, to push on stoically to the end. What he neglected to mention at the time, however, and what I suspect may have driven his decision, was that he’d spotted a Strava segment ahead and wasn’t about to let it slip through his grasp. We left Thijs to embed himself in the annals of digital cycling history and bumped ahead along the gravel track that led to the dairy. As we did, I learnt a little more about Zimbabwe’s chequered past—a past that Edward, in his 65 years, had experienced unabridged.

Edward was born just before the government of Southern Rhodesia declared independence from Britain in an act of rebellion against Whitehall’s calls for Black majority rule—a political precondition for colonies’ independence. He grew up during the Bush War, the civil conflict that erupted between Ian Smith’s ruling White minority and the freedom fighters of Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZANU) and Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union (ZAPU). His children were born as ZANU and ZAPU merged to form the ZANU Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), a party that gained power in 1980 and has won every election since. They grew up during then-President Mugabe’s Fast Track Land Reform programme, where government-funded armed gangs forcibly evicted White farmers and occupied their land. And his children’s children were born amidst the turmoil of the early 2000s, when Zimbabwe’s economy collapsed, hyperinflation ran rampant, and life expectancy plummeted by 20 years. These grandchildren witnessed the end of Mugabe’s reign following a coup in 2017, and the appointment of Emmanuel Mnangagwa in his place, a leader who’s held power ever since and who’s come under scrutiny for violations of human rights, including the abduction and torture of political opponents.

Paradoxically, but perhaps unsurprisingly, Edward remembered the days of British colonial rule with a certain fondness. He remembered times when promises were kept, where hard work was expected but fair pay was awarded, and relative economic stability was the norm. I sat soaking it in, the morally self-evident arguments against colonialism catching in my throat beside a man who’d lived this history, never benefiting, but in some times feeling less disadvantaged than in others. I wanted to apologise, to claim ancestral responsibility, but the reality was, the blame for the country’s past was far from unambiguous. Nyamoro Dairy soon emerged through the mist and I thanked Edward warmly, wishing I could do more than slip a note into his hand towards the cost of fuel. I watched as his truck rumbled away into the distance, before turning to wheel Madonna down the track towards the lambent glow of the farmhouse.

Debbie met me with all the warmth of a long-lost relative, ushering me indoors before I’d even had a chance to offer my name. Just as I was about to explain that we’d soon be joined by another, far wearier traveller, Thijs arrived and promptly collapsed on the lawn for a thorough welcome from Debbie’s black labrador. I was grateful that I could excuse myself from the front-line responsibility of meeting these slobbery advances, given my own sceptical stance on unfamiliar pets, but I did admire the scene from a distance, taking note of the clues it gave about the welcome we might be about to receive. The condition of a dog often says a lot about the hospitality of its owner. Not once have I seen a well-fed dog and been skimped by the hand that feeds it. And Debbie’s dog was, to put it lightly, robust. We stayed at the dairy for two nights, having been lulled into blissful languor by neck-deep baths, roast dinners and long evenings beside the roaring fire. It was a homeliness I hadn’t felt since, well, home, and after the trials of our first day in Zimbabwe, the comfort was intoxicating.

Though as we chatted, hunkered around the hearth, I began to glimpse a familiar weariness in Debbie, just visible beneath her warm, maternal zeal. She was a similar age to Edward and she too had endured all the challenges that the country had thrown up in her lifetime. She remembered hiding in the back of the house as her father took up arms to exchange fire with those attempting to occupy their farm. She also endured the economic collapse and subsequent loss of international agricultural contracts on which she and her workers depended. In the wake of Mugabe’s land redistribution, she faced the uncertainty of whether or not she still legally owned the land where she lived, or the livelihood that she’d cultivated. Nowadays, she too lived a life of subsistence, borrowing from friends and neighbours to pay her workers’ wages while facing the ultimate prospect of butchering her family farm into plots, just to escape the sinking spiral of debt. And things hardly looked to be getting better.

As we left Debbie’s dairy the following morning, a 4x4 with white government license plates pulled up outside her house. A local official had come to request the donation of a sheep and several tubes of milk—a valuable haul that, supposedly, would be used for prizes at a nearby country fair. The man also added to his list of demands a box of scones, complete with jam and cream, a treat for him given it’d been his birthday last week. These requests were frequent and loaded. Refusal was never an option. Whilst Debbie’s forebears had invariably benefitted in the days of Rhodesia, now, in Zimbabwe, the playing field seemed more level than ever for all but those in power or in favour. Everyone was struggling. I again felt an acute helplessness, just as I had leaving Edward, knowing that the future of life at the dairy looked bleak.

From Nyamoro we wound our way through the alpine hills of the Eastern Highlands. The road cut through dense evergreen woodland and we wrapped up tight to block out the icy breeze—a far cry from the muggy heat that had sat trapped in the basin of Mozambique. With the eerie power our senses have to transport our minds to other worlds, as the cold crept down my neck, I felt the first real thoughts of the end of this journey creeping into focus. Through the revolving door of plans and schedules that had come and gone in the last weeks, I’d banished any real thought of finishing this trip to a fanciful realm—one of imagined dreams, not sensory reality. But at some point in the not-so-distant future I’d be back in a land of four seasons. The weather would be turning, winter approaching, and the cold, which had been a remote memory for so long now, would creep once more into my bones.

And with the visions of the end finally coming into full resolution, so did the conflicting feelings that accompanied them. I felt strangely torn, strung up, swinging helplessly in the changing winds of my mind. Excitement bubbled for the adventure of the final weeks and the opportunity waiting in the blank pages of the next chapter of life, but fear too arose as I allowed openness to sour into uncertainty. We rode that day to Mutare, and the miles disappeared beneath my wheels as I let my mind be swept up in the intricate dance between the cerebral and the emotional, rationality and feeling blurring inseparably. Before I knew it, we were zipping down the final descent into the bright lights of Zimbabwe’s second city.

Mutare met us with a dazzling array of metropolitan comforts. Shopfronts with glass display windows lined the high street, traffic lights—called, rather delightfully, robots—flanked the intersections, and cypress trees studded the central reservations. Most exciting of all, large-format supermarkets—a true rarity on the journey so far—sung a siren song, beckoning us into their luminous atria to be seduced by their stacked aisles. Choice beyond our wildest dreams. Or so we thought. Like much of Africa, these aisles were symbolic of a place where everything was possible, but nothing was free. Not even close.

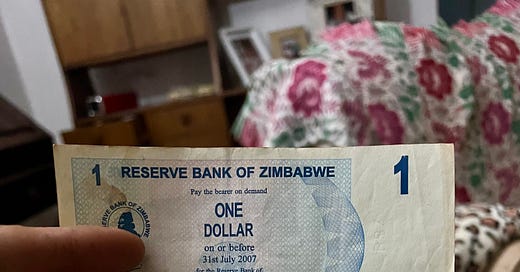

I first learnt of Zimbabwe’s struggle with the demon of inflation as a student of economics, where the country was frequently cited as the textbook example of spiralling prices. The crisis, which was the result of excessive money printing by Mugabe’s government in the early 2000s, reached its height in 2008 where prices in Zimbabwe doubled daily, culminating in an annual inflation rate of 89 sextillion percent. That’s 21 zeros. These are such colossal figures that the mind struggles to fully comprehend them, so let me explain.

If, in the year 2000—as a one-year-old—I’d decided to have a crack at early-life entrepreneurship, I might’ve bought a dairy of equivalent size to Debbie’s for about 40 million Zimbabwe Dollars (ZWD). Five years later, that same sum would cover the cost of just one dairy cow. Give it another two years and it would only buy me a gallon of milk. And, by my birthday in 2008, with that 40 million dollar fortune I’d commanded just eight years earlier, I could scarcely afford a lick of cream from the top of that gallon. At Debbie’s dairy, we’d marveled at her records from this time: her workers’ payslips, her utility bills, and, most astounding of all, her collection of banknotes. Since 2008, when the government issued the infamous 100 trillion ZWD banknote, the Zimbabwean government has made six attempts to reintroduce a sovereign currency. With such uncertainty, it’s no wonder that 85 percent of the country’s day-to-day trade is carried out in US dollars. Though the use of a foreign currency, without its lower denomination counterparts—in this case, cents—poses its own strange challenges.

In Zimbabwe’s current system, one US dollar marks the lowest denomination. So what happens when the cost of something is less than a dollar? Simple. You buy more. You want a banana? Have five. And a Coke? They’re three for a dollar. If you insist on change, then fiat money suddenly takes on a very broad meaning indeed. In ancient civilisations, cowrie shells were used as a medium of exchange. In modern Zimbabwe, boiled sweets or, occasionally, pencils, will make up the bulk of your change. Rather than stocking up on stationery during my time in the country, my Coke consumption instead rose dramatically and I was forced to develop creative methods for secreting bananas about Madonna’s person.

But the lack of usable denominations isn’t the only problem with Zimbabwe’s dual-currency system. Thanks to the persistent inflationary pressure that plagues each of the government’s new currency attempts, the US dollar also finds itself caught up in the rising tide of prices. This isn’t a novel phenomenon. Back in medieval England, in a time when money held inherent value, we also had two currencies in circulation: silver and gold. Bimetallic currencies were all the rage at the time and allowed the government to mint a greater range of denominations. But there was a problem. Whenever the government introduced a higher proportion of base metals to the mix of one coin—a method of old-school inflation called debasement: a sneaky way for governments to skim some profit from the minting process—its inherent worth would fall. With this fall, demand for the other coin would rise as people sought to preserve the value of their wealth. As this demand grew, so too would the price of the precious metal used to produce it, meaning that the coin would be more expensive to create, and the government would debase it just as they had the first. Essentially, inflation in one currency would always produce inflation in the other. And the same is true in Zimbabwe today. As demand for dollars has risen, in line with their growing popularity in day-to-day trade, so too has their price.

The upshot for us of this web of monetary complexity was that—to use the parlance of The Analyst—an hour of cycling had just become a hell of a lot more expensive. Having spent hours traipsing around the aisles of Mutare’s supermarkets, staring dolefully at the five-dollar packets of sweets, it became clear that bananas marked about the upper bound of my nutritional budget, so I bought a bunch and slunk back to the hostel where, unsurprisingly, I’d opted for the cheapest room. In this case, however, room might’ve been a tad optimistic. Sofabed-on-the-driveway-cordoned-off-by-curtains would’ve been a more accurate, though admittedly less catchy, description. Just before I drew the curtains on my quarters, our German host rushed over, asking if we’d been out in the city that evening. When we confirmed that we had, she politely advised us to remain in the compound after dark, her stricken face filling in the blanks. Mutare was apparently home to its fair share of violent crime, and the fact that the hostel timed staff shifts with the daylight spoke volumes. At that point, I began to rather regret opting for such insubstantial accommodation. I could only hope that my thrifty abode might signal a less valuable sting to the cognisant burglar.

The next day, having made it through the night mostly un-burgled—but for the blood siphoned off by the city’s mosquitos, an occupational hazard of al-fresco dozing—we set off to cover the two days to Masvingo, our next planned rest. On both days, Thijs put down a typically brisk pace, leaving me clinging to his slipstream more often than not. Though, with my vision blurred on the ground behind his back wheel, I had the opportunity to reflect on the forces at play in Zimbabwe. In a society where cash rules everything around you, what happens when it starts to lose its grip? Something else inevitably fills the vacuum. In Zimbabwe, I began to get the feeling that this new ruler was power itself. There were the powerful and the powerless; those who commanded and those who obeyed. From all I’d seen and heard from Edward and Debbie, this power was wielded with all the nonchalance of loose change, without any thought of the consequence on people’s lives. But, as I rode towards Masvingo, I couldn’t have known that I was on the brink of experiencing the plight of Zimbabwe’s powerless firsthand.

Thanks for bringing this to life Jake - such a wonderful country such a sad story.

Rhodesia or Zim was Chris Adams’s old home; how sad to read of Edward & Debbie’s reality these days XX