45. Taking the Edge Off. Part 2: Family Feasts.

30.08.24 – 01.09.24 : Amsterdam – Pietermaritzburg

If cycling through South Africa ever raised an eyebrow, then choosing a route that carved right through the centre of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), one of the country’s most infamous provinces, certainly raised the other. Aghast might well describe the reaction of many I met when they first learned of my route through their country. And with KZN home to two of the continent’s ten most dangerous cities—the top six of which are all found within South Africa’s borders—perhaps this reaction was well founded. But if I’d learned anything from the many boundaries I’d bridged on my journey so far, it was that everyone’s neighbour is a godless savage who will rob you blind and leave you for dead. And yet here I was, still seeing and still living.

But fearful fantasies often hang on the skeletons of the past. Wounds left untreated will scar. In July 2021, KZN saw violent riots erupt at the arrest of Jacob Zuma—a Zulu native, ardent anti-apartheid activist, and the country’s former leader, whose nine year presidency was peppered with allegations of political, financial and sexual misconduct. In response to the riots, and with the state unable to restore order, armed vigilantes and so-called defense squads appeared at roadblocks and shopping centres, taking public matters into private hands to quell the unrest. Politics, when harnessed as a vehicle for metronomic retribution, only serves to preserve division.

Luckily, back at Zvakanaka, I’d had Casper John—son of Casper grand—to quell my own anxieties. Having finished school, he’d cycled a similar route from his home in Limpopo down through KZN and across the Eastern and Western Cape Provinces to Cape Town, to much the same reaction. Always go in with a smile, had been his key nugget of wisdom.

But a smile is hard to conjure when faced with a day of perpetual rain. From my rondavel on a farm near Amsterdam––which, unlike its Dutch counterpart, is far from flat—I looked out over the rolling hills and a grim portrait of my day looked back. I took the tray of breakfast, delivered by the cheery farmer’s son, back to bed, to commune with my electric cocoon for a little while longer.

When, at last, I dressed, I took my time peeling on each layer, like an onion in reverse. By the time I’d finished, I was wearing all available garments, save my last pair of socks. No shred of skin was left exposed. Perhaps if I, myself, didn’t touch the Great Outdoors, I may feel as though I’d never left the nest. And, by the same logic, if I, myself, never met with the cold, tense reality of KZN, then perhaps the nagging doubts—which still lingered despite Casper John’s best efforts—might be tricked into thinking I’d stayed within safer territory. Both water and worry, however, are devious scamps and always find a way to creep in.

KZN, when it arrived, certainly looked the part. My route took me along a cracked chord of asphalt which met with fields scorched black and sky washed grey to paint a dismal scene. It wound through townships with warehouse shops, their shuttered doorways housing a tangle of life, all sheltering from the worst of the squall—people and livestock, pallets and parasols, vegetables mounded on sheets, and some not-so-live stock hung beside them. The scene felt familiar yet distorted, like a sound underwater. I cycled through under silent and suspicious observation.

By lunchtime I was empty and sought refuge in McDonalds—a placeless cathedral of homogenised capitalism, with great burgers. I opted for a Family Feast, which, as the sole fuel source of my own central heating, was a banquet of appropriately grand proportions. I stuffed the remaining burgers (yes plural, just imagine how many there were to begin with) down my bib-shorts for later consumption, hoping that, in the meantime, they might provide a little insulation. The waxed paper was a slightly uncomfortable as it tickled the soft skin of my belly, but the burgers had been warm when they went in and each emitted a pleasant cushion of heat to help ward off the creeping cold.

As I rode out of town, my newly appointed lookout—the radar rear light—picked up a vehicle coming up behind me. The small digital graphic on my GPS flashed an alarming red, rather than its usual more measured yellow. I turned to see a pickup approaching at speed. It was a new model with flash rims and opaque windows. I was already riding on the narrow hard shoulder, so it unnerved me to see the pickup drifting across the carriageway towards me. I looked ahead again to judge my margins, before stealing another glance back. Now the lights were flashing. Drifting, no, this truck was driving towards me. With purpose. I moved a little further onto the shoulder, my wheels now skirting the asphalt’s edge. By now the radar’s graphic showed the truck was all but upon me. As the digital car reached the top of my screen, and its real-world counterpart closed the gap to my wheel, I swerved abruptly off the tarmac and dropped onto the gravel beside it. The pickup passed within inches, swallowing the shoulder beneath it, before speeding off in a blare of angry honking.

From the tranquil anaesthesia of Zvakanaka, to the feast of koeksisters and naartjies shared with the travelling sales team, and the bounty of gifts bestowed by the bike shop—one of which may have just saved my life—so many in South Africa had been trying to take the edge off. Yet still it remained.

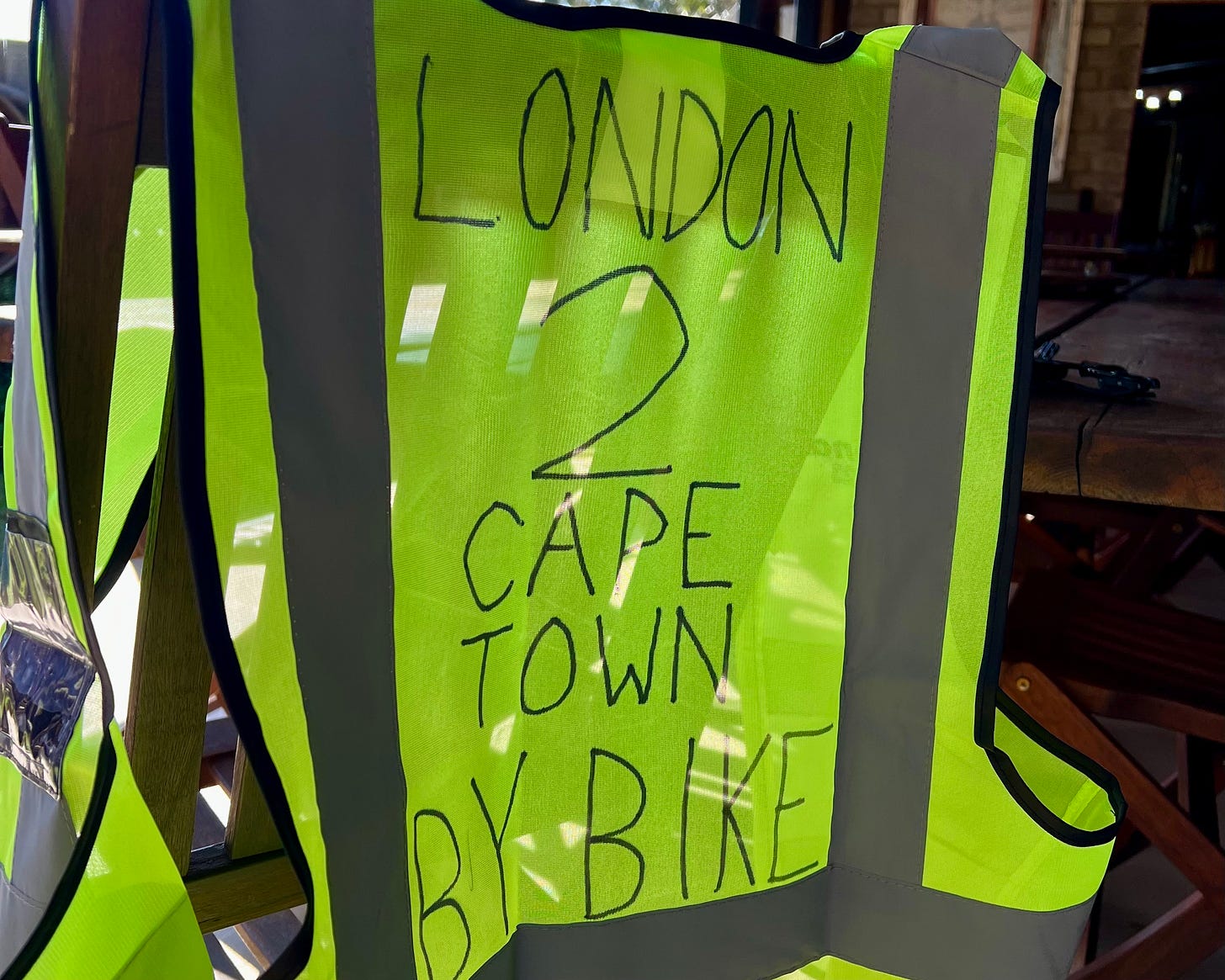

I stopped late that afternoon for a snack on an industrial estate, chewing over my worries along with my bib-warmed burger. Another pickup approached, this one all company decals and plastic reflectors. The driver leaned out of his window and asked if I’d cycled from Amsterdam that day. I confirmed I had, declining to mention that, technically speaking, I’d in fact cycled from a different Amsterdam altogether, about eight months earlier. I lacked the energy to entertain that particular rigmarole. He replied that he’d seen me on the road that morning, but that he’d have liked to have seen me better. Rummaging in the passenger footwell, he produced a package and tossed it my way. On the house! he called, giving me a cheerful wave as he edged towards the junction, indicating carefully, before pulling away. I donned the hi-vis jacket and set off myself, arms indicating my own intentions in a bid to follow his good lead.

That evening I’d booked in to stay with Jan and Carmen, a couple who’d been very receptive to the pleas of the ragged, illiquid and vivacious youth. Will you be wanting a patch of grass or a bed? the response had read, then, moments later, checked the weather – bed it is! And we’d like to have you over for supper. This cheered a soggy scamp—who was now saturated with both water and worry—and not just because it saved him the embarrassment of having to puncture the illusions of intrepid grandeur himself, by opting for the bed. He was now simply following orders.

But I needn’t have worried about my reputation. The pair were unfailingly generous with their interest in my trip, and sat enthralled, indulging my stories immensely, and the rest of me besides. At supper, seconds, thirds and then fourths were insisted, given and gratefully received—a Family Feast by any standards. I rolled to bed and gladly disposed of lunchtime’s last burger, whose wrapper had slipped off in the excitement of its carriage, and whose fillings now lined the inside of my bibs.

I landed on the decision to take a rest day at Castle Inn, Jan and Carmen’s delightful fortress. It was an extraordinary place, packed to the rafters with curiosities. A collection of artefacts—from a red London phone box, authentic American route signs, and even half a car (lazer-cut by Jan himself)—joined innumerable other knickknacks, slowly accumulated from auctions and yard sales across the country, on parade in curated chaos. Carmen was the art director, Castle Inn her chef-d’œuvre. Jan was her trusty producer, procurer, editor and transporter, sent off to source just the piece to complete each vision. They were a wonderful team and the decade-long project had carried them through a chequered time, providing a simple focus that kept them on track amidst life’s turbulence. Business complications, family tragedies, struggles with health and political unrest; all were contained just beyond the front gate, leaving home as a safe sanctuary for them to enjoy.

But the ceaseless storms were taking their toll. It was a familiar tale and one I heard often as I traversed the province. The years of Zuma’s government had been tough. The infrastructure of public life had been systematically dismantled, and the spoils distributed to those in his camp. Towns had been gutted and brought to their knees. Vryheid, where Jan had been born, grew up and where the couple now lived, had once been a jewel in the province’s crown but now litter blew through the drab, shuttered streets. Crime had shot up and security plummeted. Recently, the house of some close friends had been broken into. The parents had been held at gunpoint while the burglars searched the house. The son, in an attempt to protect them, had come out armed and was shot and killed. All for a mobile phone.

It’s inevitably tough to see beyond the act, or the actor, to the decades of repression that sowed the seeds of necessity and nurtured these crimes. In the aftermath, raw devastation and the white heat of anger congeal. You need someone to blame.

So the pair were moving, leaving their business behind and selling on their beloved project. As Jan had given a tour of the property, he’d shared this news. Everything must go. Well, almost everything. Some pieces were simply too special to lose—either that, or they’d been such a headache to source that Jan couldn’t quite face repeating the process, should the director require them again in future. The phone box, for example, couldn’t possibly be left behind. Nor could this table, nor that mirror, nor the second traffic light, nor, of course, could this gnome. It seemed that the spirit of Castle Inn would survive the move and join them on a flat-bed down to the Western Cape.

After a day at the annual German market, where I met a host of Jan’s old school friends and Carmen’s distant relatives—all the while swigging back a healthy measure of weissbier, and guzzling down the occasional sausage—we went back home to braai. As the fire tempered and the meat was left to grill, we watched the All Blacks play the Springboks. Usually a man of Proper Manners and businesslike tone, Jan was transformed. The Boks dragged their feet through the game, to a profane haranguing from the animated spectator. After each blue outburst, Jan would sit down, compose himself, and then politely ask whether something offensive might’ve slipped out. It was wonderful to watch. The Boks edged ahead by a point in the final minutes and we toasted their victory over richly barbecued meat and a bottle or two more of Jan’s weissbier. I said my goodbyes to the lovingly-crafted chaos of Castle Inn the following morning, knowing that the pair’s own farewells would be soon to follow.

By now, the rain had passed and I rode safe in the care of my protective double act, the radar rear light and the hi-vis jacket—the back of which I’d decorated with the details of my journey, in the hope it might encourage an exuberant motorist not to scupper the final leg. I made quick progress, no doubt aided by the hearty sandwiches prepared by Carmen to fuel the day’s ride. Learning from my mistakes, I kept this package—and, as a result, its contents—well away from my bibs. By the time I reached Elandsheim, a farmstay that marked the day’s objective, there was still a good deal of day left over. So, with my stay at the farm still unconfirmed, and vivacity at an all time high—following my rest day in Vryheid—I kicked on, choosing to chance my luck at a walk-in further down the road.

But from here, the landscape transformed and farmland gave way to a network of ramshackle townships. Imaginary fears surfaced once more, and I was grateful that the gradient kept in steady decline and Madonna in constant motion. With my nerves on edge, I scythed as stealthily as possible through the settlements. The only town large enough to host a guesthouse sat 40 kilometres away in the valley below. Dusk threatened to fall as I drew close, cascading behind me down the final, steep descent. At the bottom I flew into town, the momentum carrying me with purpose through the crowded streets. The bars were just opening—wooden sheds with metal grates protecting shelves stacked with hard spirits—and men hovered around them, bottles in hand. I reached the river running through Tugela Ferry, and stopped to check directions at a bridge—something I had to assume was a recent addition. Having zipped past the hotel at some point on my way in, I navigated back through the teeming town, turned off the main road and tracked a course towards its alleged location.

Arriving, I was met with an empty courtyard surrounded by closed, numbered doors. As I looked around for anything that gave even a whiff of reception, a man appeared. He bore bad news. This wasn’t the hotel. I showed him my map, the clearly pinned location, the photos of neat rows of rondavels, the pool. This place, he said, pointing at the photos, was back up the hill, about 10 kilometres by his estimate. He seemed as confused as I was about why I’d been brought here. It didn’t appear to be a regular pitfall; perhaps the usual clientele aren’t prone to dropping in unannounced. Indicating towards the numbered rooms, I asked if there might be any space for me here. I’d just spent 20 minutes coasting down the hill, I explained, and I didn’t much fancy an inverted reprise. We’re full, he replied. Christmas in Bethlehem.

So that was that. I bit my tongue and remounted Madonna, steeling myself to climb the pass in reverse, towards the only hotel not-quite-in town. The mistake had cost time, and the sun had now sunk beneath the horizon. The bars had filled out and high-spirited electricity thrummed in the air. As I pedaled back through town, my observers, still suspicious, were no longer silent. Shouts rang out around me and a small group gathered across the road ahead, waving their arms and jeering as I approached. They’d lined glass bottles along the road and were encouraging me to stop. Instead, I stood on my pedals and dipped through a chink in the blockade. The road was inclining but I accelerated, eyes trained down, not turning back, willing the shouts to recede. The shouts did recede but the bottles replaced them, launched with inebriated inaccuracy in my general direction, smashing across the road behind me. I stood on my pedals for 10 kilometres, not daring to back off from a sprint.

When, eventually, I reached the right place, it too was deserted. But at least a building marked reception loomed in the shadows and its bell, which I dinged with anxious gusto, seemed to stir some life in the back room behind it. A woman emerged, eyes glued to the phone in her hand, clearly irked by the disturbance. She dragged her feet and collapsed in the chair behind the desk, gaze still fixed on the screen, which played Reels. In response to my inquiry about a place to stay, she jerked a thumb towards a laminated price list stuck to the wall behind her. Single Room – 1000 rand. This was about the most I’d spent on a room in a year—nearly £50—and I wilted, remembering what they say about beggars. I hadn’t another option. And breakfast? I asked, hoping a buffet might emerge to soften the blow. Extra, she sulked. The balance was paid, the key was clapped down on the desk, and I left to show myself to my room. As I reached the door, I turned, adding how about dinner, do you serve that here? Yes came a muffled response from somewhere in the back room—the door had been closed behind her.

20 minutes later, after a quick scrub, I returned to find the restaurant closed and the reception locked. I ate rusks in bed and decided, as an act of wild retribution, to make a cup of tea with every tea bag on offer. Saturated once more, this time with Rooibos, I was lulled to sleep by the growls of my stomach.

I spent half the night spending a penny. A response from Jan pinged in in the early hours, who, upon learning my plans to stay in Tugela Ferry, had been characteristically businesslike in his assessment. Oh no, he’d replied, that is really not nice. Be careful. I was up at the crack of dawn and skipped a brew—it appeared I’d run out—in favour of an early departure. I was fairly keen to avoid another run in with the townsfolk, and wagered that, after last night’s revelry, not many would be awake to hear the dawn chorus. It was my penultimate day’s riding in KZN and I was headed for Pietermaritzburg—the most dangerous city in Africa.

This, however, was far from concerning. In fact, Pietermaritzburg was a beacon. There, I’d be staying with family. Well, of sorts. One of my earliest childhood friends is called Mike. Mike’s mum Wendy—as parents of children of a certain age do—became something of a surrogate mother in my last few years at primary school. Every morning I’d head over to Mike’s house at first light, often sneaking in a second breakfast in the process, and we’d walk together to school. That was, of course, apart from on snow days, when we’d sledge—and by that, I mean Wendy would pull us both along on a toboggan. If that’s not parenting, I don’t know what is. I even have a memory of arriving unannounced one Christmas morning and interrupting the day’s proceedings to compare presents with Mike. Though I imagine, on this occasion, a second meal was a step too far. The Aykroyds—as is their collective noun—hail from South Africa, where Wendy’s sister Sue has remained. She, by extension, is also family, and had invited me to stay as I passed through.

On my way over to Sue, I stopped midway for some long overdue sustenance at a Wimpy—a tasteless temple of unbridled convenience, that cooks a mean fry-up. In the typical cycle of feast and famine that characterises the uncertainty of a life on the bike, I ordered two, with a milkshake to follow.

A pair of blue cranes arced overhead as I rode the final stretch towards Hilton, Sue’s home. As they circled, I reflected on the patchwork of company you find yourself keeping while at the mercy of chance on a pedal-powered journey. Without a barrier between you and the world, you lose the luxury of choosing who you cross paths with. This is an incredible gift—it allows you to meet people where they are and discover the human first, before their political, social or moral agenda. Beyond the crust of our beliefs, often formed to protect us from the world, you find a person. And people, often, are good. But remaining open to these encounters takes energy, discernment, constant assessment. It takes removing your own crust—a challenge for us all. So to come home to family, to love unconditional, to home cooked delights, to chocolate and a wire model bicycle—given as gifts to welcome a surrogate nephew—feels terribly comforting. If there’s anything that ever truly takes the edge off, this is it.

Jake, once again I find your commentary inspiring, especially as I know it so well while cycling from Beitbridge to Bloubergstrand form 14 March to 21 April 2024. I stuck to gravel, but did go through Amsterdam and also had some "trouble" with rain! See my blog at "One Giant Challenge". Philip Erasmus

Witty, moving, disturbing and provoking - everything you can ask of a good read.