The term ancestral home might provoke in some a sense of grandeur and prestige. One might be forgiven for imagining ribbed columns supporting a proud portico, glass chandeliers suspended above a lofty foyer, perhaps even a twin staircase complete with sweeping banisters. Tracing a certain branch of our family tree, however, I’m faced with the surprising revelation that my ancestral home is a fifteen-metre-squared cave in South Africa. Now, if the Out of Africa theory is to be believed, then we can probably all trace our roots back to some fifteen-metre-squared cave or other somewhere on the continent. But in my case this happens to be a volume of slightly more recent history.

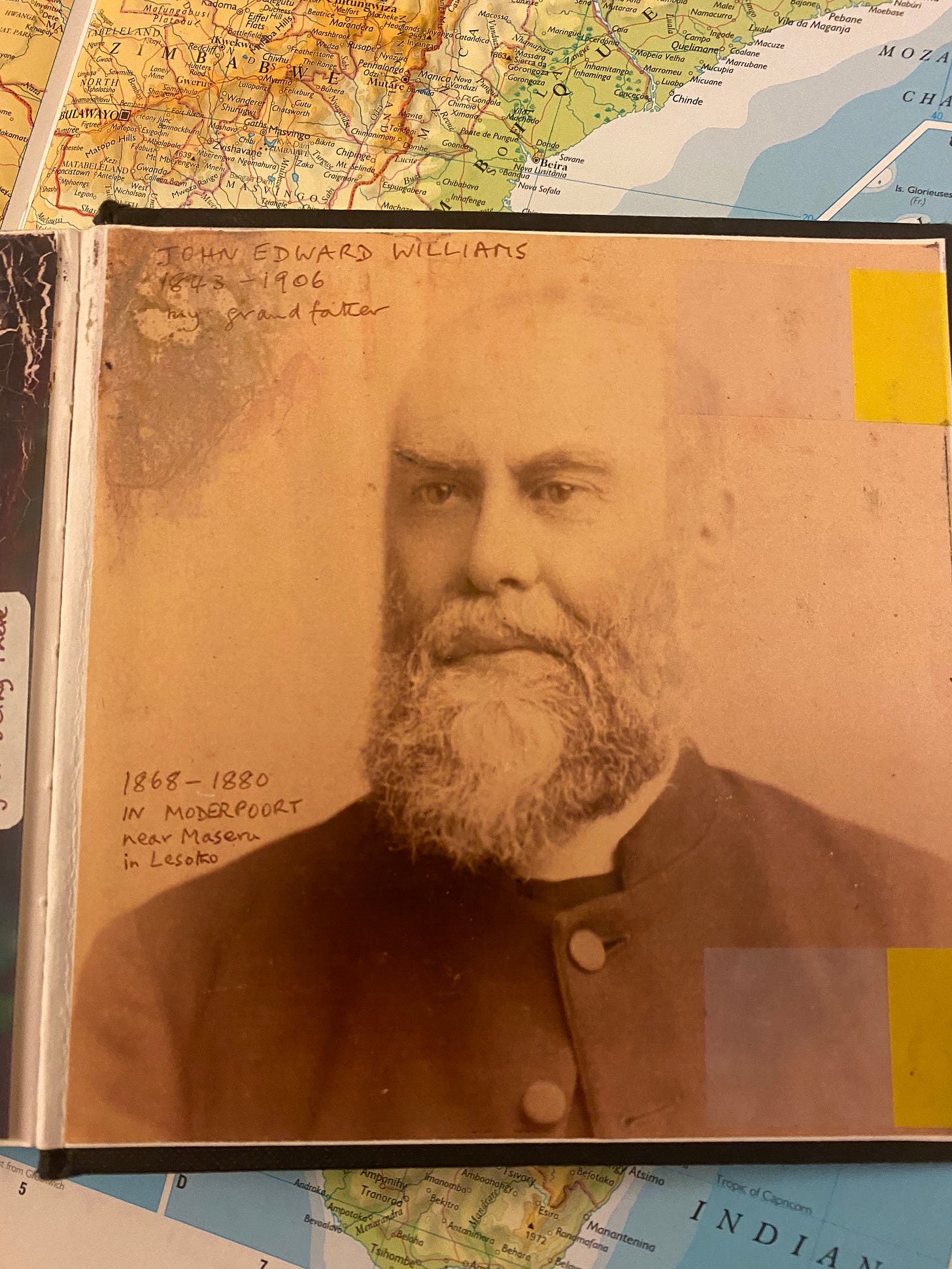

At some point in 1868, my great-great-grandfather John Edward Williams, just 20 years old, decided to up sticks and head for Modderpoort, a tiny hamlet just north of Lesotho in the Orange Free State of Southern Africa. There, along with Canon Henry Beckett and three other missionaries, he set up the Church of St. Augustine of Hippo in a small cave which doubled as their home. He lived in this cave for twelve years before his body, tired of being subjected to such austerity—even in service of a sacred endeavour like this—kicked up a fuss, and he returned to England for the sake of his health. And it’s a good thing he did, for it was only back in England that he met my great-great-grandmother, kicking off the genetic chain reaction that resulted, a century-and-a-half later, in me, standing on the doorstep of that very same cave, marvelling at the hundreds lining up outside the narrow entrance for their chance to have a peek inside.

I’d arrived back in South Africa a day earlier. Soothed by the simplicity of life in Lesotho, it struck me again the sense of subtle unease its neighbour provoked. Crossing into the modern-day Free State—a welterweight province by the country’s crime standards, but undoubtedly a heavyweight on the global scale—I took a wrong turn out of town and found myself weaving through a greyscale maze of gravel and glass, attention flitting anxiously between the digital world of my phone’s display and the physical world taking shape around me. Despite encountering nothing and no one that might arouse too much suspicion, it was alarming how quickly old worries, lying dormant, had surfaced.

I hadn’t shaken this uneasiness by the time I arrived in Ladybrand that evening, once again on the day’s final whistle. I canvassed the town centre in search of a place to stay, guided by the fluorescent pools of streetlight and lit billboards on street corners, but to no avail. Everywhere was either full, closed or beyond reasonable means. It was Saturday night and people roamed in boisterous bunches, announcing their approach with snatches of half-cut conversation, long before ghostly forms appeared through the gloom to repatriate them. Reluctantly, I broadened my search to the unlit outskirts of town, and when this was a bust, a little more reluctantly, I broadened my means instead.

After some persuasion, I was offered a special cyclist's concession for one of the fancier lodging’s lesser suites and settled my nerves with a Mission Impossible double bill and a wide selection of room service. One of the many curiosities of life on the bike—especially in South Africa, where convenience reaches near-Western extremes—is the constant oscillation between austerity and luxury, famine and feast. Your material reality shifts with such frequency that you end up living in a state of eternal impermanence. At best, this offers a chance to practice presence; at worst, it locks you in an emotional tumble-dryer. Smoothing the curve of this spiritual boom and bust requires a monkish temperament, but this was—and still is—very much a work in progress, and is probably only ever really achieved by those who forsake the trappings of modern life in favour of an existence below decks in some grotto or other.

My current material prosperity, in the wake of Lesotho’s physical austerity, soon curdled into lethargy and I spent the morning taking my rest day rather literally—huddled beneath the blankets, battling the temptation to indulge Mr. Cruise a third time. By the time I’d coaxed myself from horizontal and packed up my scattered belongings it was almost 10:30—high time to be making tracks on the Lord’s day. So, plotting a course across the ten kilometres of backcountry that separates Ladybrand from Modderpoort, Madonna and I took off towards the Cave Church.

Approaching the rural hamlet of Modderpoort—which comprised not much more than a collection of giant silos, a scattering of tied cottages and an old industrial railway station with grass growing tall between the tracks—I caught faint snippets of music carried towards me on the breeze. As I rode along a track towards the only other building in town, a conference centre that now presides over the Cave Church and its graveyard, children appeared along its verges selling sweets and assorted knick-knacks from usherette trays. At the end of the drive, women wearing flamboyant dresses and matching headscarves hurried men in shiny suits and shinier shoes to unpack elaborate picnics from car boots, while two parking attendants flapped about trying to grid cars with the futility of traffic officers in Mumbai.

I picked a path through the milling crowds using the prevailing soundtrack as my guide—a saccharine arrangement of traditional hymns spiced up by occasional livelier gospel numbers. The source, a stereo of standing speakers, sat beneath an enormous marquee fully decked out for a Sunday service. The service seemed to be wrapping up, and those in robes, who I might’ve approached to ask about the Cave Church, stood thronged by their congregation, tackling life’s Big Questions, so I ventured off solo in search of my heritage.

Thankfully, my heritage was signposted. I was directed along a network of narrow paths that wound up a small hill just behind the conference centre, dodging yet more small children, loud dresses and lustred tailoring as I went. Things became gradually more congested as I drew closer, and eventually I ground to a halt at the back of a long queue. The queue didn’t seem in a rush to animate so, leaving Madonna in line, I proceeded on foot to find out what lay ahead.

I passed swathes of young mothers who stood as diligent placeholders while children zipped between them—colliding atomically—and fathers rested in the shade elsewhere. Nearer the front, older women, clearly the most reverent, sat patiently in pole position, perched on personal, collapsible stools beside the cave’s entrance. The entrance was blocked by a door—adorned with a cross marked in dripping paint—which sat behind a gate. The gate, however, was chained shut, explaining the traffic jam. There seemed to be a typical paucity of information about when, if ever, it might be unlocked, but this did little to stunt the stream of hopefuls joining the line, which now extended resolutely down the hillside. Not being one for speculative queuing, I relieved Madonna of her duties and set about scoping an alternative approach.

The cave itself lay hidden within a large boulder which hung, half-eaten from the mouth of a steep, grassy bank. The main door led in from one side, squeezed between rock and soil, but on the adjacent face, the boulder rose proudly from the slope—its craggy skin unbroken but for a swatch of grey concrete smoothed into a narrow cleft about halfway up. Set in the concrete were another set of bars which, I could only assume, guarded an alternative ingress to the cave within. I scanned the rock, eyeing up my approach, before skipping up its face to perch on the concrete sill. Peering in through the cave’s skylight to its gloomy interior, I spotted candles flickering on a small stone altar topped with splotches of ossified wax. The low glow illuminated little else, so, with my gargoyle act beginning to attract some attention from the atomic children—who, like me, had grown impatient with the big reveal, and had now coalesced into a curious compound below—I slipped back down to ground level.

After indulging this curiosity, which saw me ferry at least half of Sunday School up the rock face in turn—pressing small rubber sandals into footholds and pointing out weight-bearing roots for grasping hands—I was approached by a woman who must have spied our expedition from her spot in the queue. Fearing a haranguing from an angry mother for having encouraged irresponsible alpine exploration, I hoisted the last of the children back off the boulder and braced for impact. Fortunately, I remained entirely un-harangued after it became clear that the woman, who had also grown tired of waiting, simply wanted a slice of the action. She was a good deal larger than my previous charges, and we wrestled for a while with the boulder before conceding that Basecamp might be a more realistic objective. Standing unsteadily on a low ledge, she posed for a picture before making a relieved retreat.

Despite, by now, having helped many of them scale the thing and steal a quick glimpse at its murky depths, I was still none the wiser as to why exactly a cave, occupied by a small group of foreigners some 150 years earlier, had attracted such a crowd. Could it be that my great-great-grandfather and his band of merry missionaries had, unbeknownst to his family, been catapulted into some sort of local stardom? Were the knick-knacks being sold from trays on the driveway in fact not knick-knacks at all but priceless religious relics—a score of sellers each offering exclusive access to one of Canon Henry Beckett’s toes? Would I, a direct descendant, upon discovery, be required to follow in the family footsteps and devote myself to a life of material renunciation and cavernous occupation?

Arriving to dispel any delusions of ancestral grandeur, and save me from a possible subterranean future, a man wandered over and sat down on the grass beside the door. Having witnessed me guiding trips up its exterior, he naturally assumed I had some authority in all matters cave-related, and asked when I might be opening things up. Forced to admit I knew almost nothing about the cave, beyond my own link to it, and why anyone—besides me, of course—might be interested in visiting, I asked what had brought him to Modderpoort. It soon transpired that he, like many, had travelled for hours that morning from deep within the neighboring provinces to join the queue waiting to set foot inside. And, what’s more, he’d never heard of the brotherhood of St Augustine, let alone Canon Henry Beckett, or John Edward Williams. He was here for Mantsopa.

The legend of Mantsopa begins in Lesotho in 1851, under the reign of the country’s first king, King Moshoeshoe—whose name I could now properly pronounce. As a middle-aged mother of four, she rose to prominence at nearly 60 after prophesying a Basotho victory over the colonising British—a battle so swift that it would come to be remembered as the Battle of Hail. Over the following decade, Mantsopa’s visions correctly predicted several more military successes, a gift that granted her great favour with the king, who came to rely on her as a close advisor. Fearing her growing influence and popularity was becoming a threat to his own rule, however, in the late 1860s, Moshoeshoe withdrew his support, exiling Mantsopa to the Orange Free State—coincidentally, at just the same time the Brotherhood of St. Augustine was taking up residence in one of the local caves.

But an encounter between the two was far from guaranteed. According to the snippets of the story that have worked their way down through my family, the missionary work of the Brotherhood was, at the time, considered progressive in its approach. The aim was not to roll out a programme of aggressive conversion, but instead to be a Christian presence in a place that was—and still is—home to a rich blend of faiths and traditions. Rather than wandering the surrounding villages on an elaborate door-knocking campaign, the brothers remained, for the most part, in Modderpoort. Nevertheless, the paths of Mantsopa and the cave-dwelling missionaries did eventually cross, for on 13 March 1870, she was baptised at the Cave Church and given the Christian name Anna, quite possibly in the presence of my own flesh and blood.

Maintaining, however, that “the way to heaven is not a narrow road”, Mantsopa practised a blend of Christian and traditional rites, continuing both to pray and prophesy well into old age. Perhaps, then, it’s no wonder that their paths did cross, and friendships flourished, with both subscribing to a more open and accepting theology. In 1906, aged 111, having spanned three centuries, two faiths and one border in a truly remarkable life, she died and her remains were buried in the graveyard outside the Cave Church, beside those of the Brotherhood who had lived and died there in Modderpoort.

Now, the cave, and Mantsopa’s grave, have become a site of pilgrimage for those of the African-initiated Zionist Christian Church who follow the prophetess’ particular brand of apostolic and ancestral veneration. At one point, animal sacrifice was common, but now visitors settle for the more tactful practice of drawing a measure of water from a holy spring—said to have been discovered by Mantsopa—a commodity that’s bottled and sold by the Church to help fund the site’s upkeep. The Prophetess’ proficiency is hardly overstated; even in death she has pioneered—with water her greatest export—something that has since become the case for her native Lesotho.

I took in this story, savouring the rich, eccentric detail of history that hangs all the more vividly on the branches of one’s own family tree. I felt keen to avoid some great proclamation of proximity or position, to lay any more claim to this ground than the others gathered there to visit it. But I felt happy to disclose my connection to this place to the man who had patiently explained his own. We shared the moment of realisation that our family paths—his sainted, motherly figure of Mantsopa, and my maternal ancestor, John—had already crossed; that our meeting was not so much an introduction as a reconnection. Overhearing our conversation, several of the older women who stood—or rather sat—guard at the front of the queue ushered me over to join them, just as a young man, dressed in an embroidered polo shirt and carrying a bristling bunch of keys, unchained the gate and swung open the door. We stepped tentatively inside.

As the light was swallowed, the cave came alive. The dusty, earthen floor; the rough-hewn rock that danced in flickering candlelight below and bled into boundless blackness above; the scorch marks of centuries of fires and candles—domestic and devotional—all breathed life into the isolated existence of those pioneers, living precariously, halfway across the world from their families, in service of some higher ideal. I felt the gruelling winter nights spent pressed together, bracing from the squalls of the impassive outdoors. I heard the echoes of candlelit compline; of the discussions, debates and disputes of a small community, crammed between rock and soil.

Just past the altar, I found myself a suitable vantage point and clambered up onto a nearby ledge, watching the stream of visitors trickle in. Reaching the altar with heads bowed, they communed with their own ancestors, petitioning them to intercede with God. Coins were offered, candles lit; at one point, even a CV was laid down—something that seems, in hindsight, to take nepotism to a whole new plane of existence. I stayed for a while, at this confluence of sacred sites, in quiet observation, before hopping down and giving the man—who had remained to help the less mobile visitors up the timeworn steps to the altar—a conspiratorial wink.

Later I heard the story of a young woman who claimed to be a direct descendant of Mantsopa and demanded, according to her ancestral rights, to take up residence in the cave, prompting an episcopal response in the form of a strongly-worded warning letter. As far as I was concerned, a glimpse was sufficient. The Bishop could save his stationary. I had neither the patience, the persistence, nor the divine perception to follow so closely in my great-great-grandfather’s footsteps. But the sense of adventure? That, perhaps, is hereditary.

Jake that's fabulous. Such a good story, and so well told. Brilliant.

Brilliant! Love those last 2 sentences! 🤣