Despite being mere days from the end, I’d made surprisingly few arrangements about how it might play out. In fact, at points, I hardly believed it would arrive at all—at least not in any way worth celebrating. I still worried that I might, at any moment, slip from the saddle, sink to the floor and admit defeat, using motorised means to cover any remaining ground. Falling at the final hurdle remained a very real possibility.

Although the peddled platitudes of today’s self-improvement slogans may claim to disagree, in my experience, more often than not, the destination steals the spotlight, leaving the journey to play second fiddle. In the early days, when explaining the aim of my imminent adventure, I was often met only with inquiries about Cape Town—Had I been before? Was I staying long?—with the small question of the rest of the continent swept beneath the conversational rug. The end, it seemed, mattered most. It was the metric of success, the mark of a challenge complete. And deep down, I harboured a nagging suspicion that anything other than a picture perfect finish might negate the months I’d spent inching across the continent; that the appraisal of this journey might be reserved for its final days. So, lest the last stint be jilted, I’d made no plan, arranged no ending, caught up, instead, in the insecurity that an imperfect challenge wouldn’t be one worth celebrating.

And yet, halfway through my semi-desert traverse, by virtue of the tendrilous networks that span our globalised world, I’d been connected with two South African locals—a journalist from Johannesburg, Mark, and a Capetonian cyclist, Jean—who had other ideas. They both thoroughly encouraged a sense of occasion; a recognition of the journey, and its destination. So, with the help of these two Evangelists, a plan began to take shape.

Mark, through his little black book of editorial contacts, managed to secure me a brief slot on a local radio station, Cape Talk, for my arrival. Jean, meanwhile, a stalwart of Cape Town’s cycling scene, had been keen to rally a mass of local riders to accompany me on the final stretch. Messaging one of the many WhatsApp groups that govern Cape Town’s group-ride timetables, bolster community fundraising efforts, and otherwise spread sentiments of general good citizenship, Jean had engaged on my behalf in earnest discussions about the safest way to reach the continent’s tip. Messages began to filter in—diligently forwarded by my man-on-the-inside—about road safety and the feasibility of arranging a police escort along a closed interstate carriageway. I worried things were getting a little out of hand.

Managing my expectations of the scale of this parade, however, Jean conceded that my planned arrival did coincide with a local annual bike race, the Greyton Pie Run, that many of the proposed mass were attending. And so the question emerged. To ride?—tackling the final highway approach flanked by flashing blue lights and a handful of Cape Town’s less racy cyclists; or not to ride?—stopping instead just short of Cape Town, throwing my hat into the ring of my first proper bike race, and banking on some goodwill for a lift to the continent’s tip. I’d spent the last Karoo days wrestling with this question, dreaming up imagined obligations and practising prepared excuses, before realising that the person who needed convincing wasn’t somewhere out there, but here, someone who’d been riding with me all along. And, by the time I’d crossed into the Western Cape, the last of South Africa’s provinces, I’d made my decision.

I spent a rest day in a quiet town, Prince Albert, whose streets pulsed with the wealth of the Western Cape—signalled as much in the presence of well-lit bakeries and dimly-lit pizza joints, as in the absence of barred windows and loose refuse. Visiting a local bike shop to fill Madonna’s tyres with self-sealing gunk in place of her perforated inner tubes—now more patch than rubber—I watched as groups of local children returned from morning rides on borrowed bikes, while others set up wash stations to clean Karoo dust from their drivetrains. Two budding mechanics helped me to strip the tubes, replace the valves, top the tyres up with sealant and reseat them with an air compressor, while two more gave Madonna a long-overdue sponge down. The owner, Arno, explained how his shop had become a hub for local children of all backgrounds, many of whom now raced at a serious level. With the work complete, the protégés gathered to offer up advice on tactics and tyre pressures. My first race was just around the corner.

I’d settled into the day’s cadence long before the sun penetrated the depths of the steep-sided gorge of the Swartberg Pass the following morning, my last of Africa’s major climbs. Between liquid murals of spiralled quartzite, I edged slowly upwards through the quiet morning, a vacuum unbroken but for the rhythmic crunch of smooth gravel beneath my tyres. A little over an hour later I gained the ridge line. And that was that; no epic battle, no grinding effort. Instead, the last climb—one of many endings to arrive over the coming days—felt something like a slow dance; the year’s festivities coming to a close. Floating down the brief descent in a flurry of tight turns, I soon reached tarmac and the gradient levelled, the landscape reclining below me as I soft-pedalled towards the horizon.

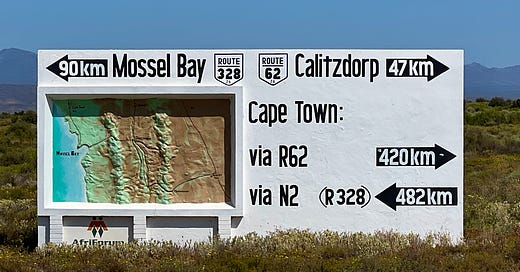

That afternoon, Cape Town appeared on its first road sign. Six months earlier, at the gateway to the Sahara, I’d found myself beneath a different road sign, one that had spelled out an exhaustive list of the cycling to come—three months distilled into a neat table of destinations and distances. It had been a significant moment at a time when the continent still stretched opaquely ahead. At the time, I wrote the following:

There’s something reassuring about seeing your destination appear on its first road sign. A subtle psychological shift takes place. It marks the moment that a destination transitions from an ephemeral geographical concept to a grounded part of the landscape you’re travelling. A definite node on the tarmac network. Keep pedalling and you’re guaranteed to reach it.

Well, in this case, not quite. It was almost amusing: to spend months pedalling furiously towards an ending, at once both unequivocal and unfathomable, only to stop short when it finally showed up. And yet, in its own way, surprising as this decision might seem, its incongruity offered a different reassurance. With the simple choice to stop short, I was breaking free of my destination, allowing the journey to reclaim its own space.

Two days later, each unremarkable in all but their proximity to the finish line, I set out on the next of my many endings: my final solo ride. Greyton lay a hundred miles away and already racers had begun to gather for the next day’s event. I spent the day as I’d spent nearly every other, soaking in the gradual and perpetual unfolding of my surroundings; pausing, periodically, to stoke the engine; and thinking, with blissful incoherence, about everything and nothing—occasionally drawing grand, profound conclusions about life and my journey, which all, inevitably, faded gently into triviality with each passing pedal stroke.

Greyton, when I arrived that evening, was a hive of activity. Bikes bristling with carbon lay, drive-side up, under an inflatable arch. Their riders, emerging from an adjacent building, brandished race packs complete with laminated numbers and sample-sized single servings of chamois cream. I leant Madonna against the rendered facade of St. Andrew’s Church, acknowledging, briefly, the fragment of connection with my family home—the vicarage of a different St. Andrew’s—where the journey began; a connection that could, I thought, form a central pillar of some great pilgrimage, if I felt compelled to make it. I did not. Instead, I hung about on the periphery, fielding the occasional question about what a scruffy waif with ten-day stubble and hairy legs was doing here, struggling to tighten the zip ties of a race number onto a forty kilogram bike.

That night, having denuded Madonna for the first time in twelve months, I sat alone in the cool night air outside a bustling bar, trying to spark a sense of occasion with a tall beer and a ceremonial cigarette. I hadn’t eaten, and the combination—especially in the context of my recent restraint—sat uneasily. The occasion failed to arise, so I returned to my room, remembering at the last moment to divert via a corner shop for some jelly beans to aid the morning’s enterprise.

I woke at the crack of dawn to a message from Jean, who had been planning to accompany me in the saddle and afterwards, whisk me the final few kilometres down to Cape Town. Although skeptical of races, and those who raced them, he’d felt compelled to enter in, so it had been decided that, in our case, the course would be ridden, rather than raced. Given that we were riding, rather than racing, we’d also opted for the shorter, 80 kilometre loop rather than the course’s full expression—the 130 kilometre Pie Run.

After twelve months of training, all on a weighted bike, with various stints in extreme heat or at significant altitude, I’d felt, admittedly, a little disappointed not to have the chance to put my legs to the test. But with this many endings, of which the race’s finish line was yet another, I’d developed a certain inertia around the specifics of each. Despite the seductive image I’d secretly indulged at times—standing atop the podium, a continent at my feet—I knew, in reality, endings rarely package so neatly. So I’d let plans emerge, resolving to enjoy the ride and to release the fantasy. But when, at 6am, the message—vehicle troubles, no travel for us—lit up my screen, the fantasy resurfaced. A race was back on the cards.

Waking up my leaden limbs, I reflected that, as races go, my preparation had been far from conventional. A precursive century, a liquid dinner, and a jelly-bean breakfast hardly seemed the stuff of serious racers. And, with Madonna in such a state of undress, I’d forgotten that some of the basics, like bottle cages, hadn’t made the cut. Dressing, I felt faintly ridiculous. My bib shorts, long past their best, had worn down to a thin gauze at the rear. Given that I’d been riding alone—and that those drivers who got close enough to catch a glimpse probably deserved the view they received—I’d failed to consider the consequences of riding in peloton. What’s more, with a Hawaiian shirt as my only clean option, whose buttons had been scattered gradually across the continent, my silhouette stood out in stark contrast to the crisp, figure-hugging outlines of my Lycra-clad competitors.

Rather sheepishly, I wheeled Madonna down towards the start line, dropping in at the village shop to replenish my jellied stash. Back outside, I was abruptly accosted by a fluorescent official standing beside Madonna. These aren’t allowed, she barked, pointing at my aerobars. I promised to take them off. And don’t even think about stuffing them down your jersey to clip on later, she continued, jerking her head triumphantly towards my laminated race card, I’ve got your number! Reassuring her that I had no jersey in which to stuff, I flew back to my room to comply. I suddenly realised that I’d returned to a world of rules. Having spent a year battling arbitrary red-tape—like Tanzania’s views on same-sex cohabitation, or Zimbabwe’s hard line on photography—I’d forgotten that, on almost all other fronts, I’d been living a life of blissful anarchy, one where hanging off the back of moving trucks and hitching a ride atop freight trains was freely permitted, even encouraged. It was a life I was fast leaving behind.

I made it to the start line with minutes to spare, wedged between riders at the back of the pack. At this point, I discovered that my only GPS mount was attached to the jettisoned aerobars. Trying, in vain, to zip-tie the device directly to my handlebars, I was saved by a woman who offered me a spare. Swings and roundabouts, I thought; rules might’ve returned, but ruthless self-sufficiency was thankfully on its way out.

The race began. It felt strange to be in such familiar motion in such a foreign context. These were serious riders, who employed subtle signals and special calls to govern their collective behaviour. At one point, climbing overzealously on what now felt to me like a featherweight bike, I received a nudge—one of the peloton’s less subtle signals—from a man in an aero helmet and large glasses, who advised I rein it in; riding as a group, apparently, meant we’d all finish quicker. And there I was thinking it was a race. It’s odd, to still feel a rookie in a sport you’ve been practising for 1,500 hours over the last year. I rode on anxiously, with my heart rate—had I a gismo to measure it—doubtless elevated.

At the midway point—by this time, fit to burst from the pressure of it all—I noticed one of the leading pack looking over and examining my cape-like shirt, before asking, are you the fella that’s ridden from London? In an instant, all was convivial. The pack—who, until this point, I’d seen only as hard-nosed machines—suddenly became people, and we exchanged cheerful acknowledgements of the absurdity of it all. I relaxed into the ride. As for my fantasy? Close, but no cigar. It was a respectable effort, though not one, I expect, that will etch my name in the annals of Greyton’s cycling history. At the finish, I took a lowly stance on one of the lesser podiums and was awarded the princely sum of a pair of socks for my effort. With that, I located Jean—who had valiantly persevered despite his uncooperative car—and was whisked away in his borrowed vehicle, Madonna packed neatly in its boot.

As we approached the night’s stopover—a self-styled Bike Hotel halfway to Cape Town—Jean informed me that the day’s activities were far from over. At the hotel that weekend was a school group, and I’d been booked as the evening’s entertainment—the keynote speaker for a dozen twelve-year-olds. The press tour had begun. Suddenly required to wrap up the last year into a neat package, tied with strands of profound wisdom about the journey and its decisive why, I retreated to my room in search of divine inspiration. With a tummy slightly funny from the morning’s injection of sugar, and a head slightly foggy with lunchtime beer, I sat down to paint a picture.

The picture that emerged was one of a year of compromises, contradictions and complaints; a journey truncated, bisected and, at times, outright skipped. It was also one of persistence, connection and vulnerability; a journey of tough decisions well navigated, of burdens shared and halved, all bound together by the unconditional kindness of strangers. It was far from neat.

I began the talk with a poem—The Naming of Bikes—which drew a chuckle from the four adults present, but a blank from the bulk of my audience. Moving swiftly on to some of my racier anecdotes, I dined out on the journey’s close calls; episodes of cuffed hands, machete-wielding demons and boar-ish pursuits. These were better received, and prompted the occasional gasp along with a flurry of porcine inquiries. Acknowledging the one girl in the audience of boys, I spoke about my partner Ellie and my friend Nadia, both of whom had come out and shown that adventures like these aren’t reserved for a particular gender. And, with a flourish, I reached my conclusion. The simplest certainty I could muster. A year distilled to a single statement.

The next morning, we checked out early, the night’s bill higher than any I’d swallowed on the journey so far. In Cape Town, we unloaded my few belongings into Jean’s granny flat—a space he’d kindly designated as temporary digs—before saddling up once again to set a course for Cape Point. Another day, another destination; with this, perhaps, the most iconic of all. I’d witnessed the pictures trickling into various WhatsApp groups throughout the last year. Jubilant endings; bunting; champagne. Exhaustive catalogues of gratitude followed by teary tributes to Mother Africa. Promises to return; never to forget.

And yet here, on the same hallowed turf, I felt almost nothing; merely a sense of mild irritation at having to pay £20 for the pleasure of existing slightly further south than I could have existed for free, to enter a place that held less significance than almost all of the ground I’d covered already. If it weren’t for Jean, I wouldn’t have bothered. But I was grateful for his nudge, if only to confirm what I already suspected: that the ending held no special significance; that the real moments of this trip happened a world away, when the thought of continuing moved from impossible to highly improbable, and I inched forwards.

A day later, the press tour continued. Lunch with Pippa Hudson welcomed me warmly into the studio, which was entirely empty thanks to a public holiday, South Africa’s Heritage Day. Ushered into the booth, I felt suddenly grateful that this wasn’t a visual medium. Despite having salvaged a button or two, my Hawaiian shirt remained just the wrong side of presentable. As Pippa segued from an ad-break, my mind searched frantically for a sound bite, something less derivative than the less people have, the more they give. Surely, there was some nugget of wisdom, something truly original, spawned from my journey, that I could share with conviction. But nothing more arrived. Like Descartes, I’d drilled down through all possible conclusions to the only tenable bedrock; the only summary I could derive. That same simple statement.

I’m not a Proper Adventurer, but I’ve had a Proper Adventure.

A Proper Adventurer would have cycled one, unbroken line, adamantly refusing assistance of any kind, and returning to the point of their last pedal stroke whenever fate led them astray. A Proper Adventurer would have dipped a back wheel in the sea at Tangier and a front wheel in the sea at Cape Point; in fact, a Proper Adventurer would have known that, on the subject of ordinal extremes, Cape Point is more of an administrative capital, whereas the official southernmost point, Cape Agulhas, lies a hundred miles further east. I am not a Proper Adventurer.

And yet, knowing who you’re not is a pretty good first step on the journey to understanding who you are. I’m not there yet. But I do know that whatever form it took, and however diffuse its delta of endings had become, the simple act of travelling alone, by bike, across the African continent, can be described as nothing less than a Proper Adventure.

You made it Rosie - what an adventure, what what a unique adventurer - not constrained by the need to pedal every meter, not bound by an unchangeable attitude to the journey, but embracing every mile, be it solo, with new friends or with old friends, but embracing the journey, embracing the adventure, embracing LIFE 🥰🥰🥰

Well done

Keep on riding 🚲

Keep on writing ✍️

Keep on embracing LIFE 🥰🥰🥰XXXXX

Thank God you are not a 'Proper Adventurer' - my goodness you write well and all that not knowing stuff sounds alarmingly like wisdom. What a great journey Jake. Well done!